Simple Questions with Complicated Answers Part 2: How do Campus GBV Complaints Work?

Written By: Deborah Eerkes

Q: How do campus gender-based violence (GBV) complaints work?

A: This is a common question, and one that has rarely been answered straightforwardly. What makes it complicated is that post-secondary institutions (PSIs) across the country have surprisingly varied structures, policies, and procedures for complaints processes.

Before I attempt to explain how campus GBV complaints work, I want to differentiate between a disclosure and a complaint. A disclosure is when a person comes forward with information about having been subjected to gender-based violence (GBV), at which point the PSI should direct them toward the supports they may need and provide options for next steps. It only becomes a complaint under one of two circumstances:

The person subjected to GBV indicates they want the PSI to initiate an investigation/adjudication process; or

The PSI decides that the matter is serious enough that it will act as the complainant itself, with or without the participation of the individual subjected to GBV.

The rest of this blog will deal with that first scenario, in which the discloser becomes a complainant. (I hope to cover the second one in a future blog post.) All campus complaints follow a similar path, but the specific procedures are established by the PSI policy and/or collective agreement(s) in place. The relationship between the PSI and the person under allegation, not the person making the complaint, determines which procedure applies. In other words, complaints about staff and faculty might be set out in their respective collective agreements, students might be subject to a code of conduct, or a GBV procedure might apply to all.

Anyone can submit a complaint under PSI policy (unless otherwise specified in PSI policy); however, there may be limitations on whether the PSI is authorized to enact its GBV policy, such as lack of authority over off-campus incidents, time limits, or cases in which the person under allegation is no longer affiliated with the PSI. In addition, there will likely be limitations on the kind of supports available if the complainant is not a member of the PSI community.

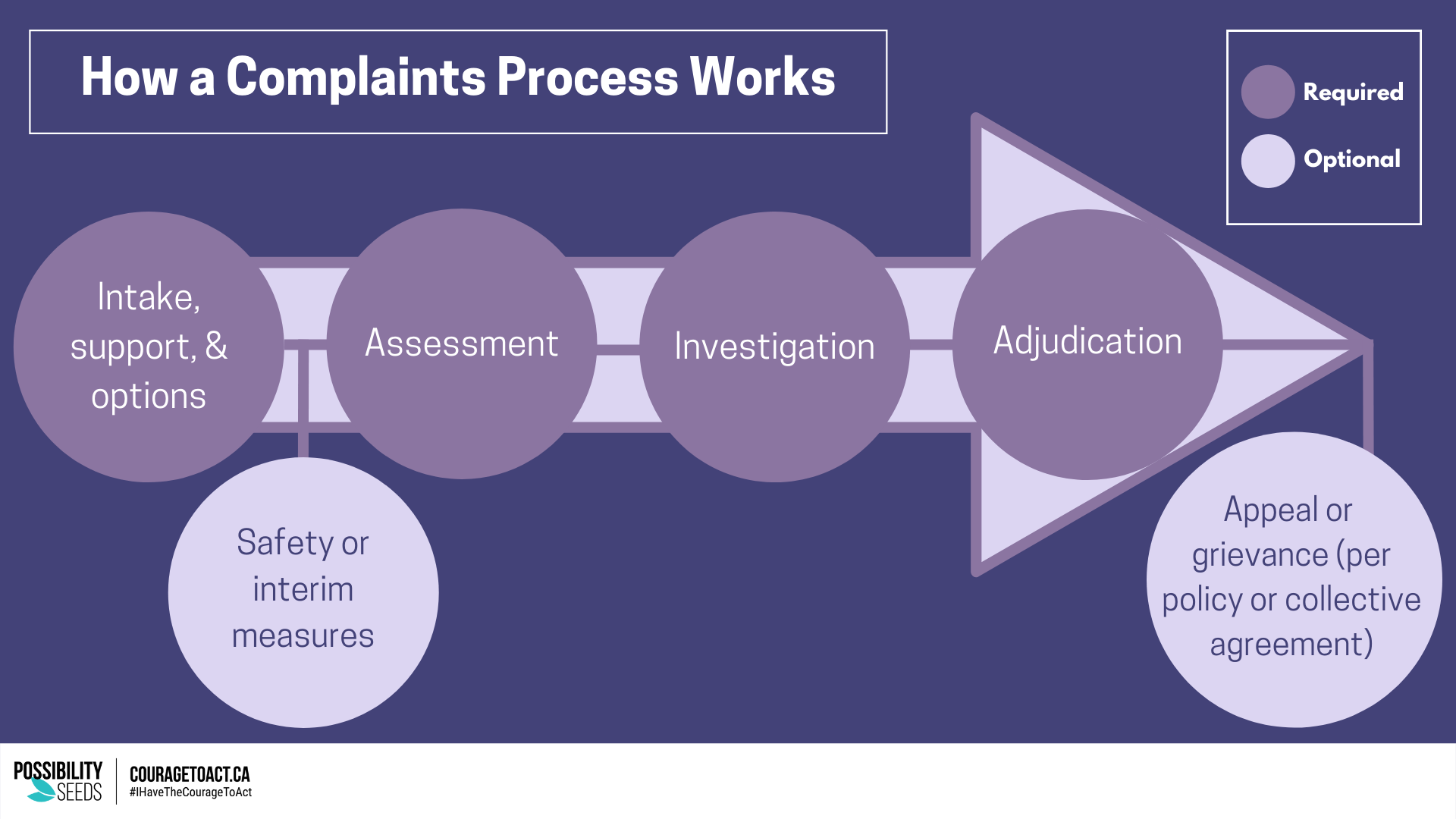

Given the wide variety of governing laws, collective agreements, and policies across the country, parties to a complaint and their advisors should look to the procedures and processes in their own institution for guidance. That said, the general trajectory of all campus complaints includes some form of intake, an assessment of safety requirements and potential interim measures, an assessment as to whether the complaints process is applicable, an investigation, and some form of hearing. Many, but not all, processes also include an internal mechanism for appeal.

1. Intake

The first step is for a PSI to support the person making the disclosure, ensuring that they understand their options and have access to whatever personal support is possible and/or necessary. This interaction sets the tone for the complainant - are they provided with enough information to give informed consent to initiate a complaint? Are they believed and treated with dignity? Are they given a range of options or simply told what happens next? Do they feel safer and confident that the PSI is taking them seriously? How they are treated at the point of disclosure may determine, in part, whether they choose to proceed with a complaint.

2. Safety

As part of the support provided at the point of disclosure, the PSI assesses the current level of risk. Is the violence ongoing? Is there evidence that the discloser or others may be subjected to further violence, intimidation or retaliation? If so, the PSI can put in place safety measures, accommodations for the complainant, and/or non-disciplinary interim measures to mitigate any possibility of further harm. These measures may also operate to protect the integrity of an investigation; for example, a non-contact order may prevent a respondent from intimidating or threatening the complainant and other potential witnesses, allowing an investigator time to gather all of the necessary information.

3. Assessment

Information collected during intake of a complaint is minimal; the discloser need only supply enough detail about the GBV for the PSI to assess whether or not the matter is within their authority. This involves two questions:

On the face of it, would the conduct described in this complaint be a violation of campus policy?

Does the PSI policy apply in the case at hand? For example, is the person under allegation subject to PSI policy? Did the incident occur in a location or circumstance in which the PSI has authority to enact the policy?

If the answer to either of those questions is “no”, the complaint cannot proceed. Regardless of the answer to these questions, the PSI should provide the complainant with access to support and other options.

4. Investigation

A trauma-informed, procedurally fair, neutral, and timely investigation is the backbone of a campus GBV complaint. A skilled investigator creates the conditions for all participants to provide the best quality information possible, organizes the information gathered into a cohesive narrative, and evaluates the reliability and credibility of information received. As if this weren’t difficult enough, a skilled investigator must also challenge personal biases and be sensitive to inequities that need correcting. They must be savvy enough to apply all of the correct legislative standards and procedural requirements, and to avoid improperly importing notions from the criminal legal system. Investigators in some PSIs make recommendations to a decision-maker; others are responsible for the determination as to whether the subject of the complaint was in violation of policy. In the latter case, the section below applies as well.

5. Adjudication

A thorough and detailed investigation report provides the foundation for the PSI to make a decision as to what happens next. Adjudication involves two decisions: a finding as to whether the respondent has violated PSI policy and a what form sanctions or disciplinary action might take. Generally, both of these decisions, regardless of who makes them, involve an opportunity for the parties to state their case (which can take any number of forms, including a one-on-one meeting, written submissions, or more court-like hearing) to an unbiased decision-maker (an individual, panel, or tribunal). The decision-maker may focus only on outcome in cases where the investigator has been tasked with making the finding.

6. Review or Reconsideration

The final step in a campus complaints process is the opportunity for both the respondent and the complainant to challenge the decision(s). This could be internal, in the case of an appeal to a different decision-maker, or external, for example in the form of a grievance by the union that results in arbitration. The relevant statutes, policies, procedures, or collective agreements lay out what may be appealed and by whom, as well as the nature of the appeal (for example, review on the record, appeal on specific grounds, or fresh re-hearing) and who makes the decision. Once all internal appeal or grievance mechanisms have been exhausted, parties to the matter can turn to the courts for judicial review.

Astute readers will have noticed a glaring omission: not once have I mentioned the police. If you read my previous blog entry, you’ll know that this was intentional. Criminal complaints to the police and campus complaints under policy are best kept entirely separate. While going to the police should be presented to disclosers as an option, campus complaints should not be confused with, contingent on, or modelled after a criminal process.

For detailed strategies to ensure that processes are procedurally fair, trauma-informed, and that they work to reduce harm at each of these steps, see A Comprehensive Guide to Gender Based Violence Complaints, available at couragetoact.ca/knowledgecentre.

The Reporting, Investigation and Adjudication (RIA) Working Group focuses on formal campus gender-based violence complaints processes, with an aim to infuse trauma-informed practice into procedurally fair processes and reduce the harm to complainants, respondents, witnesses, and all staff and faculty involved in the process, from disclosure through to appeal. The RIA Working Group is one of three Working Groups with the Courage to Act project. Each Working Group is composed of experts in their respective fields from across Canada. The RIA Working Group’s membership includes Deborah Eerkes and Britney De Costa, with contributions from Zanab Jafry.

__________

Suggested Citation: Eerkes, D. (2022, January). Simple Questions with Complicated Answers Part 2: How Does a Campus GBV Complaint Work? Courage to Act. www.couragetoact.ca/blog/simple-questions-part-2.