Sexual Consent Education at Canadian PSIs

Sexual Consent Education at Canadian Post-Secondary Institutions

Written by: Dr. Scharie Tavcer

For years I have studied sexual violence. And for years it’s an issue that divides people in the room. Whenever I tell folx what I research they either dive in, discuss, and debate, or they deflect and walk away. That’s okay because I remain passionate about studying sexual violence and I am comfortable with the discomfort.

In recent years Canadian post-secondary institutions (PSIs) received pressure to respond to this violence. Unfortunately only British Columbia, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Ontario, and Quebec provincial governments passed legislation mandating their PSIs to establish stand-alone sexual violence policies and protocols. In the United States, there are federal laws that ensure PSIs have strategies in place to prevent and respond to sexual violence but researchers acknowledge that more state-level and localized legislation is needed (Karjane, Fisher, & Cullen, 2005).

Lately, the discussions revolve around whether universities should have sexual consent education and if so, should it be mandatory? Mount Royal University (MRU) in Alberta for example, only offers consent education (and other sexual violence programming) on an in-person and ad hoc basis to anyone who seeks the info, and it is one part of a larger educational program for Resident Advisors and other student leaders. And the current provincial government has not passed legislation to mandate violence-informed policies, protocols, and/or consent education. They have however slashed the budgets of all PSIs across the province. One (of many) consequences to those cuts has resulted in the dissolution of our Centre for Equity and Meaningful Inclusion (CEMI) and our Sexual Violence Coordinator (SVC) is now the sole person responsible for programming and services for the campus community with the help of volunteers.

Now in case you didn’t know, the prevalence of sexual assault in Canada has not really changed in +30 years and the reporting of victimization has only waxed and waned over that same time period (Benoit et al., 2015; Brennan & Taylor-Butts, 2018; Conroy & Cotter, 2017). The lack of reporting is consistent across North America in that only 1 in 10 sexual assaults is reported to police (Brennan & Taylor-Butts, 2008; Department of Justice, 2017; Krebs et al., 2011; Tjaden & Thoenees, 2000).

Reporting for 2018, more than 11 million Canadians had been physically or sexually assaulted since the age of 15 (Cotter & Savage, 2019). This represents 39% of women and 35% of men, with the gender difference driven by a much higher prevalence of sexual assault among women than men (30% versus 8%) (Benoit et al., 2015; Cantalupo, 2011; Fisher et al., 2000; Holland & Cortina, 2017; Karjane et al., 2002; Tjaden & Thoeness, 2000). One in ten (11%) women students experienced a sexual assault in a postsecondary setting in 2019 (Burczycka, 2020; Fisher et al., 2000) and more than 90% of those victims do not report to school authorities (Burczycka, 2020).

In response to these facts, I ask what can be done differently – what can PSIs do to reduce the numbers of victims and potential perpetrators? What can be done in the face of dwindling budgets and lack of access to programs and services?

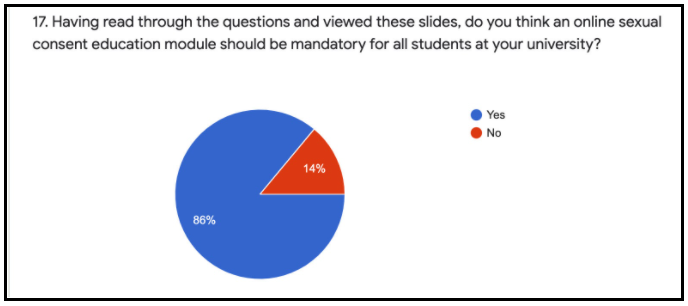

I began my study about sexual consent education by taking an inventory of what is currently offered at over 100 PSIs across Canada. Then I asked students at seven PSIs to explain their understanding of consent, what consent education exists at their university, and who receives that education? And I also asked them if consent education should be mandatory for students and/or mandatory for everyone on campus (faculty, staff, and administrators)? Thanks to COVID I had to switch data collection to electronic surveys and to date, but thankfully over 100 students from those seven PSIs have responded.

Findings so far tell us that students have a mixed understanding of what is consent. This is troubling for many reasons. Students also express that they want consent education, and that they want everyone on campus to get that education. They talk about wanting a #CultureOfConsent that permeates all corners of their university.

I want that too. But how can this be realized when resources are cut, when positions are eliminated, when CEMI exists only in name, and when the SVC is expected to gather volunteers to do the work of many? Regardless of the cuts to post-secondary education in Alberta, some SVCs and academics like myself, are working together to create consent education for students or for employees. Other PSIs across Canada already have various types of online consent education (Concordia, McGill, UManitoba, UToronto, USaskatchewan to name a few). In Alberta, Bow Valley College has a student-focused education module, and MacEwan University and NAIT are currently creating an online module directed at employees.

If we truly want to change the prevalence statistics, if we want a campus that is informed and safe, if we want to support victims and potential victims, if we want to deter potential perpetrators... then we need to do things differently.

One of the outcomes from my research is to craft an online consent education module that will aim to bring us towards a #CultureOfConsent. The module will have several sections and the first edition will be directed at students - all students. Subsequent editions will be for employees. We haven’t yet decided if it will be mandatory or not. The draft table of contents looks like this:

Introduction

Introduction video of President and/or Provost welcoming the user and what are the benefits of taking the module

Video of PSI’s sexual violence centre/coordinator welcoming users and declaring the importance of this module

Instructions

Summary slide of what is ahead including a certificate at the end and deadlines

How to navigate the module [can stop and return in more than one sitting]

Feeling overwhelmed button, self-care, accountability, and support

The Facts

What is sexual violence? What does the law & my PSI’s policy say?

Statistics of various groups including BIPOC & marginalized persons

What is consent? What does the law & my PSI’s policy say? Various types of consent and things that vitiate consent

Examples and quiz questions

Victims and Survivors

Under-reporting, barriers to disclosure, and responding to disclosures

Male victims, BIPOC & marginalized persons

Emotional, physical, and psychological impacts of SV

Where and what resources are on and off campus

Intoxication and Consent

Giving and receiving consent

What does the law & my PSI’s policy say?

How do you know? Scenarios

Examples and quiz questions

Power Dynamics

Who has power? Types of power. What does the law & my PSI’s policy say?

Power and consent. Giving and receiving consent. How do you know?

Rolling with rejection

Scenarios and quiz questions

The Bystander Effect

What is it and what you can do to stop SV or help someone at risk

The 6 D’s: deflect, distract, detach, delay, document, debrief, delegate

Scenarios and quiz questions

Certificate of Completion and Thank You

I’ve met with the President and Acting Provost at Mount Royal University who both support its creation. The module will be an online tool and it has several topics (content with an Indigenous lens, that is trauma-informed, intersectional with BIPOC and trans-identified persons, responding to rejection, intersects with employee policies, addresses power imbalance and more) all of which is supported by research and in consultation with other experts. The first-edition of the module will be ready this year. My hope is that the value and need for consent education will no longer be a dividing topic. And my hope is that discussions will take place for it to be mandatory for an entire campus community.

__________

References

Benoit, C., Shumka, L., Phillips, R., Kennedy, M. C., & Belle-Isle, L. (2015). Sexual violence against women in Canada. Status of Women Canada.

Brennan, S., & Taylor-Butts, A. (2008). Sexual assault in Canada in 2004 and 2007. Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics.

Burczycka, M. (2020). Students’ experiences of unwanted sexualized behaviours and sexual assault at postsecondary schools in the Canadian provinces, 2019. Catalogue no. 85-002-X. Statistics Canada.

Cantalupo, N. C. (2011). Burying our heads in the sand: Lack of knowledge, knowledge avoidance, and the persistent problem of campus peer sexual violence. Loyola University Chicago Law Journal, 43(1), 205-266.

Conroy, S., & Cotter, A. (2017). Self-reported sexual assault in Canada, 2014. Catalogue no. 85-002-X. Statistics Canada.

Cotter, A., & Savage, L. (2019). Gender-based violence and unwanted sexual behaviour in Canada, 2018: Initial findings from the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces. Catalogue no. 85-002-X Statistics Canada.

Department of Justice Canada. (2017). Justice Canada Knowledge Exchange on the Criminal Justice System’s Responses to Sexual Assault Against Adults – Summary of Proceedings.

Holland, K. J., & Cortina, L. M. (2017). “It happens to girls all the time”: Examining sexual assault survivors’ reasons for not using campus supports. American Journal of Community Psychology, 59(1-2), 50-64.

Karjane, H.M., Fisher, B.S., & Cullen, F. T. (2005). Sexual assault on campus: What colleges and universities are doing about it. U.S Department of Justice National Institute of Justice.

Krebs, C.P., Barrick, K., Lindquist, C.H., Crosby, C.M. Boyd, C., & Bogan, Y. (2011). The Sexual Assault of Undergraduate Women at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Journal of Interpersonal Violence 26(18).

Tjaden, P., & Thoenees, N. (2000). Prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women: Findings from the national violence against women survey. U.S Department of Justice.

__________

Suggested Citation: Tavcer, Scharie. (2021, February). Sexual Consent Education at Canadian PSIs. Courage to Act. www.couragetoact.ca/blog/sexualconsenteducation